Beech Hill House Crash: 22nd October 1944

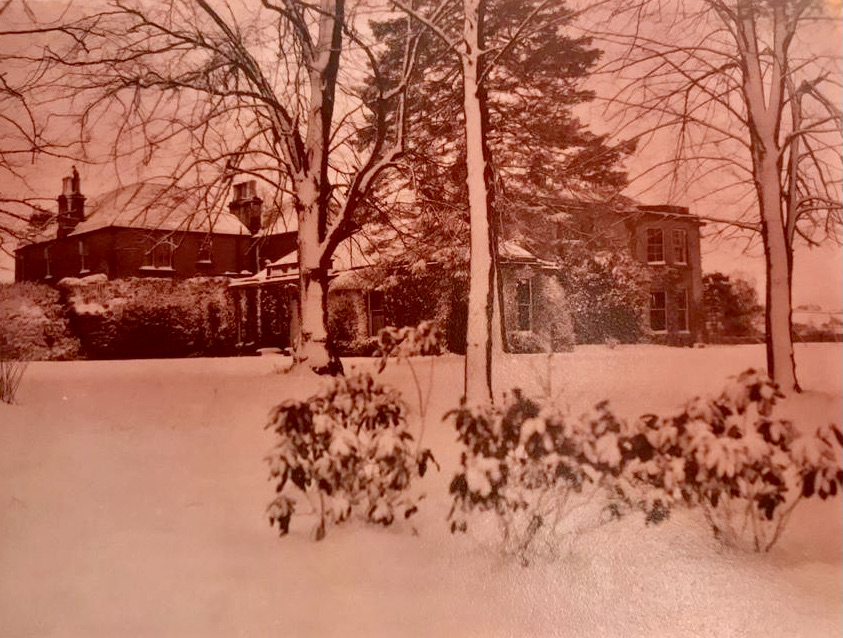

South face of Beech Hill House prior to the crash.

The house lies to the south of Haddington, just off the main road to Gifford. The Mosquito hit the upper storey of the house on the left of the picture.

[Courtesy of A. & P. De Pree]

The north side of Beech Hill House.

[Courtesy of A. & P. De Pree]

RAF Training in East Lothian

RAF East Fortune was employed as a base to train aircrew, first in the night-fighter and later in long-range fighter and strike roles. Both necessitated significant hours spent flying at night, a process sufficiently complicated and dangerous in itself but further complicated by wartime blackout conditions, the often inclement weather, unreliable equipment and the sad fact that aircraft sent to training squadrons were often well-worn and tired.

It was to be the last factor that led to the crash of de Havilland Mosquito, T. MkIII, LR559, operated by 132 (C) O.T.U. on the night of Sunday, 22nd October 1944.

The crew

Flt/Lt Iain MacPherson (128638 RAFVR) was twenty-six years old. Before enlisting in 1941, MacPherson had been a policeman in Rutherglen for four years. He had been born in Airdrie, the second son of Mr and Mrs David MacPherson of 120 Stirling Street, and was a former pupil of Airdrie Academy. Tragically, the family had already lost his brother, Neil, killed at sea two years previously. The ripples of pain and loss travelled further, as Iain had only just married Elizabeth Hobbins Moxon, a secretary and driver for the Women's Auxiliary Police Corps, a mere three months previously.

When Iain joined up he had been sent overseas to train in the Southern Rhodesian Air Training Group, organised as part of the Empire Air Training Scheme. Over 8,000 aircrew were trained in Rhodesia during the war years. He had then been posted to East Africa before coming back to the UK in July 1944, either for further training or as an instructor on the Mosquito at East Fortune.

RAF East Fortune was employed as a base to train aircrew, first in the night-fighter and later in long-range fighter and strike roles. Both necessitated significant hours spent flying at night, a process sufficiently complicated and dangerous in itself but further complicated by wartime blackout conditions, the often inclement weather, unreliable equipment and the sad fact that aircraft sent to training squadrons were often well-worn and tired.

It was to be the last factor that led to the crash of de Havilland Mosquito, T. MkIII, LR559, operated by 132 (C) O.T.U. on the night of Sunday, 22nd October 1944.

The crew

Flt/Lt Iain MacPherson (128638 RAFVR) was twenty-six years old. Before enlisting in 1941, MacPherson had been a policeman in Rutherglen for four years. He had been born in Airdrie, the second son of Mr and Mrs David MacPherson of 120 Stirling Street, and was a former pupil of Airdrie Academy. Tragically, the family had already lost his brother, Neil, killed at sea two years previously. The ripples of pain and loss travelled further, as Iain had only just married Elizabeth Hobbins Moxon, a secretary and driver for the Women's Auxiliary Police Corps, a mere three months previously.

When Iain joined up he had been sent overseas to train in the Southern Rhodesian Air Training Group, organised as part of the Empire Air Training Scheme. Over 8,000 aircrew were trained in Rhodesia during the war years. He had then been posted to East Africa before coming back to the UK in July 1944, either for further training or as an instructor on the Mosquito at East Fortune.

Flt/Lt Iain MacPherson (128638 RAFVR)

[Thanks to Arthur Bannister for this photograph]

Flying with MacPherson on the 22nd October was another Scottish pilot, Warrant Officer Peter Turvey Wilkinson, aged twenty-three (1348307 RAFVR), son of Colin and Beatrice Wilkinson of Boswall Green, Edinburgh. It isn't known who was at the controls at the time of the explosion, but given the difference in age, rank and flying experience, it's probable that Wilkinson was under MacPherson's instruction.

Warrant Officer Peter Turvey Wilkinson (1348307) RAFVR

The crash

The two pilots took off from East Fortune on a training flight on the 22nd October just before eleven on a fairly filthy winter's night: it was raining heavily. The pilot banked to overfly Haddington but, only minutes after take-off, the aircraft suffered a catastrophic explosion in a fuel tank. The crew was given no chance of recovering the situation as the Mosquito, already at a low altitude, fell swiftly out of the sky hitting a tree, the ground and a garden wall before the main part of the wooden plane hit the west wing of Beech House. The impact demolished much of that section of the old building and that which was still standing was immediately set on fire. The crew was killed instantly. Wreckage was scattered over a wide area with one of the engines ending up a quarter of a mile away.

Flt Lt Iain MacPherson is commemorated on Column 2 of Glasgow Crematorium while W/O Peter Wilkinson is buried in St Martins Graveyard, Haddington.

The two pilots took off from East Fortune on a training flight on the 22nd October just before eleven on a fairly filthy winter's night: it was raining heavily. The pilot banked to overfly Haddington but, only minutes after take-off, the aircraft suffered a catastrophic explosion in a fuel tank. The crew was given no chance of recovering the situation as the Mosquito, already at a low altitude, fell swiftly out of the sky hitting a tree, the ground and a garden wall before the main part of the wooden plane hit the west wing of Beech House. The impact demolished much of that section of the old building and that which was still standing was immediately set on fire. The crew was killed instantly. Wreckage was scattered over a wide area with one of the engines ending up a quarter of a mile away.

Flt Lt Iain MacPherson is commemorated on Column 2 of Glasgow Crematorium while W/O Peter Wilkinson is buried in St Martins Graveyard, Haddington.

W/O Peter Wilkinson's gravestone, Haddington, St Martins

The civilian casualties

We know of only six civilian casualties suffered by East Lothian residents from aircraft crashes during the war. The loss of Mosquito LR559 at Beech Hill House was to cost four of those lives, which sadly made it the deadliest such event for civilians during the war. The civilians killed by the crash or fire included:

Mrs Ruth De Pree (75) She lived in Beech Hill with her husband Lt.-Col. Cecil George De Pree, whom she had married in 1897. He survived the crash as he was downstairs at the time and he survived till February 1948. Ruth was a niece of Sir Douglas Haig, First Earl Haig of Bemerside, as she was the eldest daughter of Mr Hugh Veitch Haig of Ramornie, Fife, Earl Haig's brother. Her husband was Earl Haig's nephew.

She had been living in Saughton House, Edinburgh, during the First World War when her husband was on active service. A fire in February, 1918, destroyed the house entirely and forced her to look elsewhere for somewhere to live. After a short search Ruth had found and moved to Beech Hill House. Her husband, Cecil, and Francis Mortimer, estate gardener, had tried to reach her room using a ladder but the fire spread too quickly and this proved impossible.

Lt Col. John Haig D.S.O. (66) He was on a visit from his home at Carnoch, Glen Urquhart, Inverness-shire. He was Ruth De Pree's brother. He had been sitting downstairs with Lt.-Col. De Pree when the plane struck and had rushed upstairs to try to reach his sister. He must have perished in the fire and his body was never found. John Haig had had a distinguished career in the army during the First World War. He had seen service in Egypt with the Westminster Dragoons Yeomanry in 1914 and had served thereafter in Salonica, the Western Desert and Palestine. He was present when Jerusalem had been captured and came to command his regiment in France when it was converted into a machine-gun battalion.

David George Pitcairn (5) son of Mrs Ruth Goda Pitcairn, daughter of Cecil and Ruth De Pree. The war had already widowed Goda when her husband, Andrew Alexander Pitcairn, was killed while second in command of the 2nd Battalion of the Black Watch, when it was part of the breakout from Tobruk in 1941. David was their only son. He had previously, as an acting Lt.-Col., commanded the 2nd Battalion during the defence of Crete.

Daisy Spiers (50) Daisy was the nanny/nurse looking after David. She came from Langshaw, Galashiels.

Also in the house but unharmed were:

Sarah Baxter, Cook, and her son Jackie (3 1/2). She was blown out of bed by the force of the initial crash and explosion but had had time to grab her son before the flames cut off escape.

Lt.-Col. Cecil George De Pree - as mentioned above. He had been a professional soldier n the 15th Hussars and the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry at the outbreak of the war in 1914. After war service during the First World War he had ended his career as a Lt.-Col in the Labour Corps in 1918.

William Miller, butler.

Francis Mortimer (gardener) and his wife. Francis had gone to help Cecil De Pree when the latter attempted to use a ladder to reach Ruth's bedroom. Francis gave the following eye-witness account to a reporter from The Scotsman newspaper:

"I heard the plane and remarked to my wife, who was already in bed, 'Don't you think that plane is flying very low?' I thought it was making a forced landing, and then I heard a crash and came running out in my underclothes and bare feet. I saw what I thought was a parachute falling but one of the police officers told me it was probably the 'plane's dinghy. It was not more than fifty feet high. I never thought for a minute that the house had been struck and was on fire. Then I heard terrific explosion, and I looked towards the house and saw that it was an inferno.

I rushed to the kitchen to warn the staff, and met Colonel de Pree. 'Get a ladder', he said. I got a ladder from the harness room and put it against the front wall. I was about four rungs up, when flames rushed out from the window. It was hopeless. Colonel De Pree was going to climb the ladder himself, but it would have served no purpose.

He had been sitting with Colonel Haig in a room downstairs. Colonel Haig ran to his sister's bedroom and was not seen again. The nurse apparently ran to the boy's room."

Mrs Ruth Goda Pitcairn, daughter of Ruth and Cecil De Pree. Her life was saved by the lucky happenstance that she had gone to the kitchen to fill a vacuum flask which someone had forgotten to fill. Her desperation for her little son can only be imagined and a policeman had to physically restrain her efforts to get into the house to try to save him.

We know of only six civilian casualties suffered by East Lothian residents from aircraft crashes during the war. The loss of Mosquito LR559 at Beech Hill House was to cost four of those lives, which sadly made it the deadliest such event for civilians during the war. The civilians killed by the crash or fire included:

Mrs Ruth De Pree (75) She lived in Beech Hill with her husband Lt.-Col. Cecil George De Pree, whom she had married in 1897. He survived the crash as he was downstairs at the time and he survived till February 1948. Ruth was a niece of Sir Douglas Haig, First Earl Haig of Bemerside, as she was the eldest daughter of Mr Hugh Veitch Haig of Ramornie, Fife, Earl Haig's brother. Her husband was Earl Haig's nephew.

She had been living in Saughton House, Edinburgh, during the First World War when her husband was on active service. A fire in February, 1918, destroyed the house entirely and forced her to look elsewhere for somewhere to live. After a short search Ruth had found and moved to Beech Hill House. Her husband, Cecil, and Francis Mortimer, estate gardener, had tried to reach her room using a ladder but the fire spread too quickly and this proved impossible.

Lt Col. John Haig D.S.O. (66) He was on a visit from his home at Carnoch, Glen Urquhart, Inverness-shire. He was Ruth De Pree's brother. He had been sitting downstairs with Lt.-Col. De Pree when the plane struck and had rushed upstairs to try to reach his sister. He must have perished in the fire and his body was never found. John Haig had had a distinguished career in the army during the First World War. He had seen service in Egypt with the Westminster Dragoons Yeomanry in 1914 and had served thereafter in Salonica, the Western Desert and Palestine. He was present when Jerusalem had been captured and came to command his regiment in France when it was converted into a machine-gun battalion.

David George Pitcairn (5) son of Mrs Ruth Goda Pitcairn, daughter of Cecil and Ruth De Pree. The war had already widowed Goda when her husband, Andrew Alexander Pitcairn, was killed while second in command of the 2nd Battalion of the Black Watch, when it was part of the breakout from Tobruk in 1941. David was their only son. He had previously, as an acting Lt.-Col., commanded the 2nd Battalion during the defence of Crete.

Daisy Spiers (50) Daisy was the nanny/nurse looking after David. She came from Langshaw, Galashiels.

Also in the house but unharmed were:

Sarah Baxter, Cook, and her son Jackie (3 1/2). She was blown out of bed by the force of the initial crash and explosion but had had time to grab her son before the flames cut off escape.

Lt.-Col. Cecil George De Pree - as mentioned above. He had been a professional soldier n the 15th Hussars and the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry at the outbreak of the war in 1914. After war service during the First World War he had ended his career as a Lt.-Col in the Labour Corps in 1918.

William Miller, butler.

Francis Mortimer (gardener) and his wife. Francis had gone to help Cecil De Pree when the latter attempted to use a ladder to reach Ruth's bedroom. Francis gave the following eye-witness account to a reporter from The Scotsman newspaper:

"I heard the plane and remarked to my wife, who was already in bed, 'Don't you think that plane is flying very low?' I thought it was making a forced landing, and then I heard a crash and came running out in my underclothes and bare feet. I saw what I thought was a parachute falling but one of the police officers told me it was probably the 'plane's dinghy. It was not more than fifty feet high. I never thought for a minute that the house had been struck and was on fire. Then I heard terrific explosion, and I looked towards the house and saw that it was an inferno.

I rushed to the kitchen to warn the staff, and met Colonel de Pree. 'Get a ladder', he said. I got a ladder from the harness room and put it against the front wall. I was about four rungs up, when flames rushed out from the window. It was hopeless. Colonel De Pree was going to climb the ladder himself, but it would have served no purpose.

He had been sitting with Colonel Haig in a room downstairs. Colonel Haig ran to his sister's bedroom and was not seen again. The nurse apparently ran to the boy's room."

Mrs Ruth Goda Pitcairn, daughter of Ruth and Cecil De Pree. Her life was saved by the lucky happenstance that she had gone to the kitchen to fill a vacuum flask which someone had forgotten to fill. Her desperation for her little son can only be imagined and a policeman had to physically restrain her efforts to get into the house to try to save him.

The gravestones of Ruth Haig and Cecil De Pree, Morham Church

(D. Haire)

The official response

The Scotsman report also included reference to the official response to the crash. The reporter wrote of the speedy arrival of firemen from Haddington, one of whom borrowed a car from the house and drove to a neighbouring farm where he was able to phone the Edinburgh brigade for assistance. They arrived twenty-five minutes later.

Having heard the explosion, an Air Force unit arrived from one of the local stations and brought a foam-sprayer. All this effort did succeed in saving the servants' quarters and several rooms in the main house.

The police also attended, with one saying that he had seen the plane in flames over Haddington. The Scotsman reporter continued:

"The ruined wing was still smouldering late yesterday afternoon when N.F.S. men, who had been on duty since the early hours of the morning, were turning over the rubble. A mobile canteen was in attendance serving meals. The Haddington A.R.P. Rescue and Repair Services and the Leith N.F.S. Salvage Corps were employed on the burned-out fabric. Dr Campbell, Medical Officer for the County of East Lothian, was present yesterday afternoon helping to identify the bodies."

The Scotsman report also included reference to the official response to the crash. The reporter wrote of the speedy arrival of firemen from Haddington, one of whom borrowed a car from the house and drove to a neighbouring farm where he was able to phone the Edinburgh brigade for assistance. They arrived twenty-five minutes later.

Having heard the explosion, an Air Force unit arrived from one of the local stations and brought a foam-sprayer. All this effort did succeed in saving the servants' quarters and several rooms in the main house.

The police also attended, with one saying that he had seen the plane in flames over Haddington. The Scotsman reporter continued:

"The ruined wing was still smouldering late yesterday afternoon when N.F.S. men, who had been on duty since the early hours of the morning, were turning over the rubble. A mobile canteen was in attendance serving meals. The Haddington A.R.P. Rescue and Repair Services and the Leith N.F.S. Salvage Corps were employed on the burned-out fabric. Dr Campbell, Medical Officer for the County of East Lothian, was present yesterday afternoon helping to identify the bodies."

Beech Hill rebuilt.

[Courtesy of A. and P. De Pree]

After the crash.

The damage to the house was such that it was decided to demolish the main building and rebuild it. The family moved into the servants' quarters as the rebuilding process, with its attendant legal matters, was going to take some time. The architect for the new house was Lindsay Jamieson and it was completed by 1953. Some of the stones from the old building went into the construction of Nunraw Abbey.

The damage to the house was such that it was decided to demolish the main building and rebuild it. The family moved into the servants' quarters as the rebuilding process, with its attendant legal matters, was going to take some time. The architect for the new house was Lindsay Jamieson and it was completed by 1953. Some of the stones from the old building went into the construction of Nunraw Abbey.